Top 30 Backyard Birds

Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI

|

Chestnut-backed Chickadees |

In Part 1, we covered the five most common feeder birds. Part 2 then took a little bit of a detour from your backyard seed feeder to discuss some beautiful and celebrated birds that mostly don’t eat seed. Now we return to the center stage of the backyard with five more very common visitors to seed, suet, and peanut feeders. While these birds will eat sunflower seeds, they all have a particular fondness for nuts—especially the woodpeckers. This can be connected to the common provenance of these birds: their natural habitats are our oak-rich forests and woodlands where acorns are a major food source.

Some of these birds have adapted very well to typical residential neighborhoods, while others generally require some remnant native oaks nearby. One thing the oak forest origins of these birds means for us is that we can particularly appeal to these birds by offering suet or peanuts, foods that are rather less attractive to the abundant finches which often dominate seed feeders.

11. Oak Titmouse

|

|

Identifying: Titmice are very plain, but at the same time both easily recognizable and highly endearing. In brief: they are grey. A bit lighter on the front than the back, and sporting a little pointed crest or mohawk (the pointiness of which will vary as the bird goes about its daily business). Their voice is also a familiar sound, making some rather nasal, raspy, chickadee-like calls along the lines of tsick-a-dee or see-jert-jert! see-jert-jert! (Visit Cornell's All About Birds to hear some examples.)

Worth noting: Titmice are probably the most successful of these birds at adapting from native oak-dominated communities to oak-less residential neighborhoods (although they do need some trees). Most yards will host a pair; titmice mate for life and defend a territory year-round, so you won’t see flocks like you do with house finches and goldfinches. If you have an older field guide, you may see them listed as “Plain Titmouse;” this is the same bird, with the old “Plain” species split into today’s “Oak Titmouse” and the very similar “Juniper Titmouse” which lives east of the Sierran crest.

|

Chickadee eating Bark Butter. |

12. Chestnut-backed Chickadee

Identifying: Chickadees and titmice are fairly close relatives and have some similarities of diet, voice, and behavior. As a group, what distinguishes the chickadees from their titmice cousins are their dark caps and bibs, divided by a white cheek. Our only local chickadee is the Chestnut-backed Chickadee, which adds a rich brown color to its back and sides, completing its distinctive multi-toned plumage.

Worth noting: Chickadees are generally ranked among the foremost competitors for the “cutest bird” title due to a collection of endearing traits: they are tiny (smaller than House Finches, and rounder), they cling and perch in upside down and other circus trick positions, they make a lot of charming squeaky calls, and they are often quite approachable. They are moderately common in residential neighborhoods, though not universal; the more native trees around, the better your odds of attracting them.

13. Downy Woodpecker

|

|

Identifying: We’re covering the three most common woodpeckers here—one of the easiest ways to tell them apart is to look at their backs. On the Downy Woodpecker, the back is white, appearing as a vertical white bar between the black of the two folded wings. (Nuttall’s Woodpecker back is horizontally striped; Acorn Woodpecker back is plain black). Downies are our smallest woodpeckers, with a rather short and dainty bill.

Worth noting is the existence of another woodpecker, the Hairy Woodpecker, which is notoriously tricky for beginning birdwatchers to distinguish from the Downy Woodpecker. First, Downies are much more likely in most local backyards, while Hairy Woodpeckers can be seen most often in conifer forests, such as on Inverness Ridge and Mt. Tam. Visually, Downies are both smaller and have proportionately smaller beaks; Hairies are bigger and have significantly bigger beaks. These comparisons are hard to be confident with until you’ve seen both a few times, but if it strikes you as a very small woodpecker with a petite little poker of a beak, then it’s probably a Downy.

14. Nuttall’s Woodpecker

Identifying: Striking horizontal white bars on the back ("zebra stripes") make this woodpecker easy to identify. (The closely-related, official “Ladder-backed Woodpecker” is a bird in the southwest US and Mexico.) Slightly bigger than Downy and quite common if you have some native oaks nearby.

Worth noting: Their loud, dry, rapid 2-syllable calls often alert you to their presence before you see them. (Hear it at All About Birds.) As with Downy (and Hairy) Woodpeckers, only males have a red patch on the back of their heads (juveniles, like the lower bird in this picture, have a red patch on the front of their heads). This is pretty common among woodpecker species. Nuttall’s Woodpeckers are named after Thomas Nuttall, an early 20th century naturalist who wrote an influential early field guide and had the rare honor of being quoted in Part 2 of “Top 30 Birds” series.

15. Acorn Woodpecker

Identifying: The most distinctive of our woodpeckers. As mentioned above, they have a plain black back, but that probably won’t be the first thing you notice about them. Instead it will probably be their “clown” face, with bold white patches on their black heads. They are larger than either of the two previous woodpeckers and very vocal, with a loud, repeated two-syllable “crazy laugh” call, often audible from several birds at once. Unlike the others described here, both males and females have red on their head (on females as shown here it is only on the rear of the head; on males it extends all the way to the white forehead).

Worth noting: Hikers are often impressed by the sight of “granary trees” where Acorn Woodpeckers have cached thousands of acorns, most often in dead trees, but sometimes in manmade structures such as wooden utility poles. Unlike other woodpeckers, they live in colonies, with other birds besides the parents helping to raise the young and guard the acorn granaries.

Acorn Woodpecker. Local picture by Pat DuMond. |

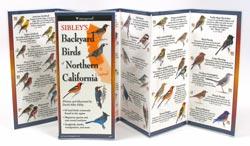

Featured Product: Sibley's Backyard Birds of Northern California

|